History's New Look

Renovated Antietam National Battlefield Visitor Center Opens Doors, Eyes to the Past

By Guy Fletcher

Photography by Bill Kamenjar

For decades, staff and many visitors at Antietam National Battlefield knew too well about the notorious support column that stood inside the front entrance of the park’s visitor center. The pole’s awkward placement, in the middle of a busy lobby, was more than an eyesore.

“People ran into it,” says U.S. Park Service Ranger Keith Snyder, the battlefield’s chief of resource education and visitor service.

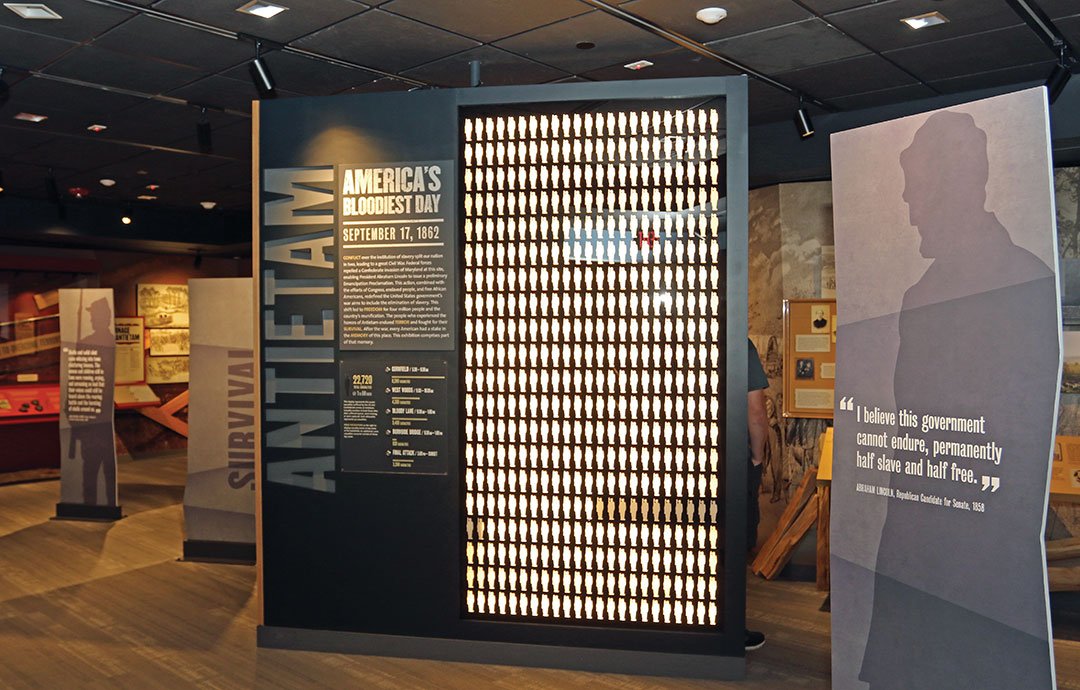

A lighted, interactive board helps visitors understand the massiveness of the casualties of the battle.

It was no surprise, then, that when staff discussed what they wanted to include in the planned renovation of the center, one of the first comments was: Get rid of the pole. To their relief, it was removed and replaced by a support beam that now stretches across the building, unseen, above the ceiling.

Removing the pole illustrates that the main focus of the nearly completed $8 million visitor center renovation—a massive project that rebuilt and expanded the building and reimagined its telling of the Battle of Antietam through new exhibits, stories, and interpretations—was simply making the battlefield more accessible.

Just a few feet from the site of the former lobby pole is an elevator that can take guests to a lower-level exhibit area or upstairs to an observation deck offering an expansive view of the battlefield. Snyder points out that visitors who struggled with steps were once directed by staff to walk around the building on the sloping ground as their only means to reach the observation area.

“The biggest driver in the rehabilitation of this building was to make it more accessible,” he says.

HALLOWED GROUND

Antietam National Battlefield is among the crown jewels of the U.S. Park Service’s Civil War catalog, with its 3,200 acres of finely preserved or restored grounds. In fact, except for the ubiquitous monuments, markers and statues that dot the park, the battlefield’s rolling grounds appear very much the way they did on Sept. 17, 1862, when U.S. and Confederate armies clashed in what is considered the bloodiest day in American history.

A newly discovered map shows the mass graves on the battlefield.

On that day, Confederate soldiers under Gen. Robert E. Lee battled with U.S. Gen. George B. McClellan’s federal forces in fighting that would rage from dawn until late afternoon. It was the Civil War’s first major engagement on Union soil and resulted in nearly 23,000 dead, wounded or missing. Though the Union forces suffered more casualties, the battle is generally considered a victory for the federal army because of its strategic and political implications.

Today, the Antietam battlefield represents something of the gold standard in Civil War preservation. Two-thirds of the current park didn’t even belong to the U.S. Park Service before 1990. But an aggressive effort to save, expand, and protect the battlefield—buffered by restrictions on local development—have given it the reputation as one of best restored battlefields in the nation. Unlike some other locations, there are no motels or strip shopping centers nudging up against hallowed ground here.

But while the battlefield has grown and flourished—now greeting some 300,000 visitors a year—its 60-year-old visitor center has had its struggles. A leaky roof gave the building a damp, musty feel, while a faulty septic system was known to back up from time to time. The trademark wood trellises in front of the building rotted after years of exposure to the elements. Exhibits and artifacts were informative, but narrowly focused.

Dunker Church was the focal point of a number of Union attacks against the Confederate left flank.

“We loved the building, but it had a lot of problems,” Snyder says.

Planning for the renovation was years in the making, beginning with an advisory group of historians, academics, park staff, and others, including the NPS’s chief historian and former chief historian. “We basically locked ourselves in a room, twice, for three days” to put together a vision of what a new center would look like, Snyder says.

Construction began in January 2021, with the building already closed due to COVID-19 restrictions. The building had all its outdated mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems removed, along with everything else. “Basically, every inch of this building was stripped to the walls,” Snyder said.

From the top of the visitor center, patrons have a panoramic view of the battlefield, where they can relate the distant geography to a relief map on the table.

To accommodate visitors during construction, a temporary center was built. Offices, artifacts, and staff were moved across the parking lot to a block of seven trailers.

An important factor in the project was the battlefield’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places, which prevents any changes to “character-defining features.” For example, the trellises in front of the building had to stay, but they are now made of metal. “It will never rot,” Snyder says. Inside, particular attention was given to the limestone walls and slate floors because the lobby was expanded, and new materials had to match.

TELLING A BROADER STORY

The renovated visitor center keeps many of the artifacts in updated exhibits, but others were added, with an emphasis on accessible, interactive, and hands-on displays. For example, the observation deck now includes a raised relief map of the battlefield that visitors can touch to understand the topography that soldiers fought over.

One new exhibit uses the lighted images of bodies that illustrate the number of casualties at Antietam; visitors push buttons to indicate the number of killed, wounded, and missing from various phases of the battle.

Behind the light display is an 1864 map that shows burial locations on the battlefield. The bodies of nearly 6,000 soldiers were originally buried at Antietam before being re-interred at cemeteries and other locations. But it wasn’t until 2020, when researchers found the map in the New York Public Library, that its existence was even known. “This burial map had never been seen before,” Snyder says.

A new map helps visitors understand the geography of the battle view of the battlefield.

Work to improve access through the exhibit area required cutting through three feet of concrete, since part of the lower level was designated a fallout shelter during the Cold War. The former shelter now serves to highlight five themes of battlefield: conflict, terror, survival, freedom, and memory.

While in the past the park might have stressed the actual battle very well, the five themes allow it to address larger, broader questions about the battle’s cause and consequences, as directed by the advisory group.

“We are trying to have the broadest possible story reach the broadest possible audience,” Snyder says.

That’s because Antietam is part of a larger story that is centuries in the making. It begins with the growth of slavery in the colonies and continues with key events in secession, the war itself and construction and long after that. Antietam can be credited with inalterably changing the moral path of the war. The battle’s result gave President Abraham Lincoln the political leverage to issue, just five days later, the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation—re-directing the war from conflict to preserve the Union to a crusade to free enslaved people.

“We decided this is the appropriate place to get into these broader concepts,” Snyder says.

NOT THE SMITHSONIAN

The idea, he explains, is for visitors to first learn the themes in the artifacts and exhibits so they have a fuller understanding when they explore the actual battlefield. “This isn’t like the Smithsonian,” Snyder says. “You don’t come in here [to the center] just to walk around and go home.”

In fact, visitors begin learning the story even before they walk through the center’s doors. The long, serpentine walkway from the parking lot—built to improve accessibility up a steep hill—is embedded with a timeline of Civil War battles and other important events.

The second-most popular question visitors ask staff is whether the Battle of Antietam took place before or after the Battle of Gettysburg, so the sidewalk provides that answer—Antietam took place nearly a year before Gettysburg—even before they walk through the front door. (The most popular question directed to battlefield staff is, “Where are the restrooms?”)

“We knew we had to do this long, winding sidewalk, so we wanted to make it interpretative,” Snyder says.

About halfway up the walkway, visitors are greeted by a new wayside marker and sculpture of a Confederate and Union soldier titled, “Exposed to the Fire of Slavery and Freedom.” They tell the story of Sgt. William H. Paul of the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry, who risked his life to recapture his unit’s flag in Miller’s Cornfield, site of some of the deadliest fighting of the battle.

As Snyder looks around the gleaming new center, he laments there are still some small jobs that need to be done after the “soft opening” in August. There is also some landscaping work needed and the site of the temporary visitor center needs to be restored. “We are not 100 percent,” he says, pointing to a small nick in the panel in need of paint.

The goal is to be as close to finished as possible by the middle of September. Anniversary weekend typically draws thousands of visitors from across the county. Arriving that day will certainly be many people who are repeat visitors to the battlefield, who knew the old visitor center very well. Some might have had a literal run-in with the pole.

“We basically brought this historic building into the 21st century,” Snyder says.